A delicate dance: The Kalahari, fire and climate change

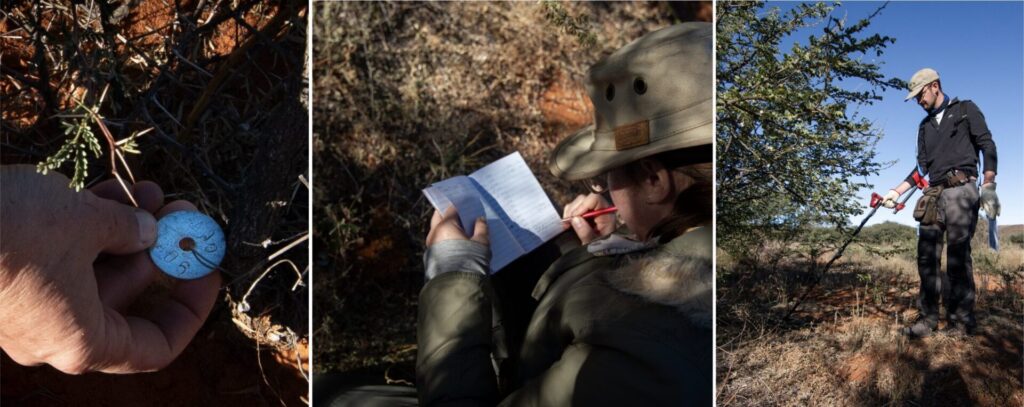

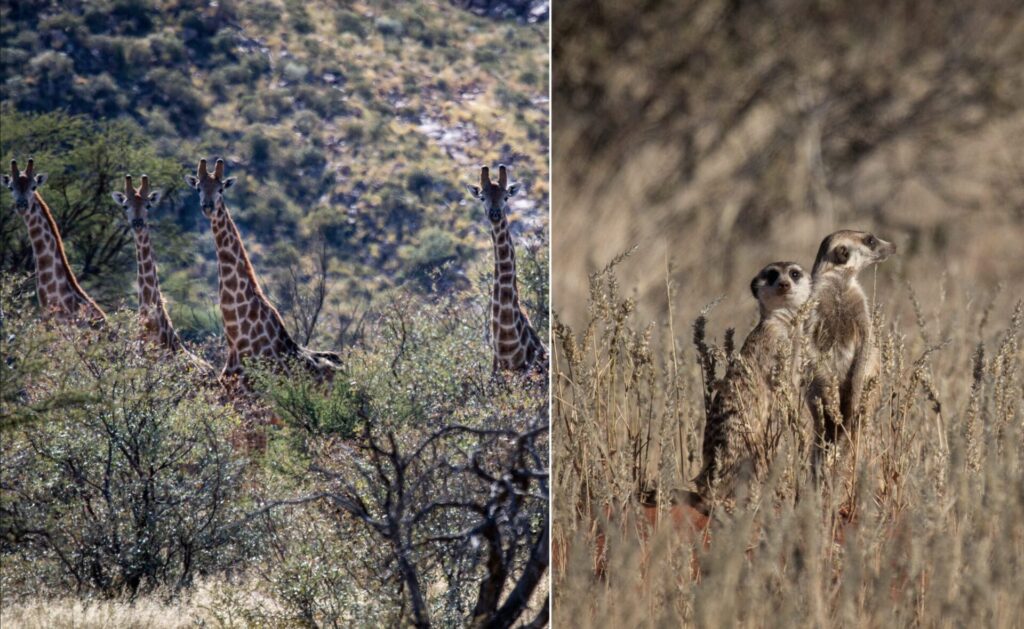

The morning sun beats down, dispelling the winter chill at Tswalu. Prof Susi Vetter, her face creased with determination, pushes through a thicket of thorns to gather data. Beside her, Dr Tiffany Pillay thoroughly records every observation, a testament to the comprehensive nature of their work. Curious giraffes watch their progress with gentle eyes. Over a thousand plants are tagged across the study area, a daunting task that requires both patience and precision. Much like a treasure hunt, MSc student Jordan McCullough sweeps the ground with his metal detector, searching for the faintest signal of a buried seedling tag from previous years. Meanwhile, PhD student Bridgette McMillan carefully excavates, ensuring no trace of these botanical time capsules is missed.

What drives this meticulous fieldwork? The answer lies in understanding one of the Kalahari’s most powerful natural forces – fire.

Tswalu’s fire ecology project, a long-term study in its third year of fieldwork, was spearheaded by researchers from Rhodes University and the University of Pretoria. The team working on this project aims to unravel the complex interplay between fire and the landscape, especially in light of recent years of above-average rainfall, which has raised concerns about the likelihood of fires.

Tswalu lies in the southern Kalahari, a vast expanse of semi-arid land in the northernmost reaches of South Africa. This unique ecosystem is shaped by fire and rain, affecting biodiversity, nutrient cycles, and species interactions. Characterised by drought cycles interspersed with years of good rainfall, this fragile balance gives rise to the southern Kalahari’s colloquial name, the Green Kalahari.

The region is warming faster than the global rate, with climate predictions showing a gradual drying trend, leading to more droughts. Rainfall, although infrequent, significantly influences fire dynamics. Seasons of high rainfall cause grasses to grow lush and tall, increasing fuel load. The grasses dry out over the winter, and lightning storms in spring and early summer can set the waving fields of grass alight. Hot, dry and windy conditions (which will become more common as temperatures rise) can turn vast areas into combustible fuel, making them more vulnerable to uncontrolled burns.

While the vegetation of the Kalahari is adapted to cope with the extremes of a semi-arid climate, the increased unpredictability of rainfall and longer droughts are creating new risks for habitat regeneration. By examining how specific plant species respond to fire, scientists aim to better understand how this ecosystem will cope with these changing conditions.

The research team has established 12 plots of 25x25m across Tswalu bushveld, tagging all individual plants of camel thorn (Vachellia erioloba), black thorn (Senegalia mellifera) and grey camel thorn (Vachellia haematoxylon). Each species provides unique insights into fire resilience and adaptation. Camel thorn is a keystone species with slow-growing and rare reproduction from seed; while black thorn reproduces en masse after good rain (which can be a problem leading to encroachment); and grey camel thorn, a favourite food for black rhinos, although it rarely reproduces from seed, seems to regenerate vigorously after fire. For each tagged plant, the team annually records fruiting, flowering, and developmental stage.

Grasses are an essential part of the ecosystem, providing forage for herbivores and fuel for fires. Bridgette McMillan’s PhD research focuses on assessing the flammability of different grassland types at Tswalu and their recovery after burning. This is an important part of her research as it illustrates how fires affect the grass layer, including its ability to produce forage for wildlife after fires.

Different grass species vary in flammability, influenced by factors such as age, moisture content, and chemical composition. When vegetation is dominated by highly flammable species, fires tend to spread more easily and with greater intensity. Although the flammability traits of many southern African grass species have been well documented, those of the dominant grasses in the Kalahari, such as Stipagrostis uniplumis, Eragrostis pallens, Aristida stipitata, Centropodia glauca, and Schmidtia kalahariensis, remain unknown. The grasses typical of the Kalahari differ markedly from those found in other South African savannahs and grasslands; even widespread species such as Digitaria eriantha exhibit a notably different growth form in the Kalahari compared to other regions. This represents a significant gap in current research.

The distribution of grass species across Tswalu’s varied habitats adds another layer of complexity. All species play a unique role in this intricate ecosystem, and the interplay between herbivores and natural processes like fire and plant growth adds an extra layer of complexity to the ecological relationships within the reserve.

Herbivores, the silent architects of this landscape, wield a powerful influence in shaping fire dynamics. Their appetites, a delicate choreography of consumption, sculpt the very fabric of the grassland. By favouring certain grasses over others, they can transform the vegetation, either creating a dense fuel bed that invites fire or cultivating a more resilient landscape that can withstand the flames.

The future of fire in the Kalahari is still being uncovered by scientists; however, they agree it is likely to be shaped by several factors, including climate change, rainfall patterns, vegetation composition, and grazing practices, all of which have direct implications for the ecological balance of the ecosystem.

The findings of the Tswalu fire ecology project will be instrumental in guiding fire management practices within the reserve, helping to ensure that this ecosystem remains resilient in a changing climate. Furthermore, the project will contribute valuable data to a global initiative aimed at understanding the impacts of warming and drying conditions in other regions.

About the author:

Inaê Guion is a Brazilian biologist and conservation photographer. Holding a PhD in Applied Ecology, her work blends scientific research with compelling visual storytelling to advocate for environmental preservation, focusing on the intricate connections between nature, humanity, and conservation.

Images: Inaê Guion and Marcus Westberg