The value of collaring mesopredators at Tswalu

The thrill of radio-tracking wild animals is something that etches into your memory, a pulse-quickening blend of anticipation, skill, and sheer wonder. Scanning the landscape with telemetry equipment, ears tuned to the faintest beep, communicating with your monitor to pinpoint your target. Navigating the reserve’s maze of dirt roads and sandy trails, your eyes search for fleeting silhouettes amidst the grasslands. The animals we seek are masters of evasion, amplifying the thrill of the chase.

As the sun sinks low over Tswalu, winter’s chill begins to bite, and darkness envelops the landscape. Bundled in thick coats, gloves, and beanies, with flashlights at the ready, I join my fellow researchers from the Tswalu Foundation’s research centre for a nighttime endeavour. It’s 11 pm when we reach the designated junction near the Tshukudu waterhole, the vehicle’s engine falling silent as we kill the lights. In another vehicle, Tswalu’s wildlife team is also on standby. Hidden in a makeshift shelter, ecologist Dr Wendy Panaino and vet Marnus De Jager stand ready, waiting for the clan to approach. The Champions League match flickers on a mobile screen – Real Madrid versus Borussia Dortmund – and we’re all hoping for a Vini Jr. goal. While Wendy and the vet remain vigilant, with no time for idle waiting, the rest of us find a welcome distraction in the game, a moment of connection in the cold, unfamiliar night. Finally, the radio crackles: the animal has been darted. What follows is a flurry of motion. We converge on the scene, our flashlights cutting through the darkness to reveal the sleeping form of a spotted hyena – a subadult male. The team works swiftly to fit the animal with a radio collar, ensuring it’s snug enough to stay in place but loose enough to avoid discomfort. ID photos are snapped, measurements taken, and with the collar secured, the vet administers the wake-up injection. We wait, hearts pounding, until the hyena stirs. With a groggy shake, it rises and melts back into the night, leaving us with a sense of quiet triumph.

Attaching a device to reveal an animal’s movements and activities across the landscape offers a practical approach to tracking. Radio collars, equipped with transmitters, batteries, and antennas, have their weight carefully calibrated never to exceed 3-4% of the animal’s body mass. The data these collars provide is invaluable, offering insights into daily movements, home ranges, social interactions, and dietary habits. Each transmission tells a story, and because each collar operates on a unique frequency, researchers can track multiple individuals simultaneously, weaving together a complex narrative of life in the wild.

For private reserves like Tswalu, collaring is about conservation and safeguarding the future of these species and the ecosystems they inhabit. Tracking devices yield key understandings that inform management practices, optimising veterinary care, reducing human-wildlife conflict, and even deterring poaching. Crucially, in areas bordered by farmland, location data reveal when an animal strays beyond reserve boundaries onto agricultural land, allowing for proactive intervention to mitigate potential conflict with farmers and protect both livestock and wildlife.

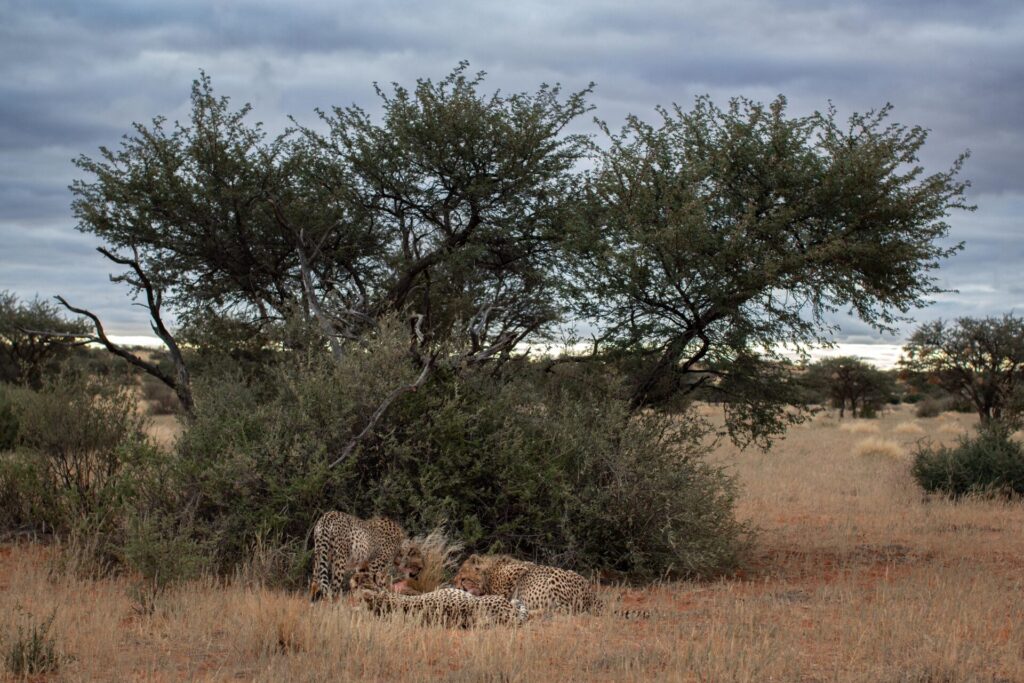

Tswalu is a sprawling expanse of wilderness where large carnivores have been reintroduced and now thrive. Maintaining this balance, however, requires careful human intervention. The cheetah population, for instance, has flourished in the reserve.

Since 2022, around 50 cheetahs have been relocated from Tswalu to other reserves across South Africa and beyond, a vital source for the country’s cheetah metapopulation. This metapopulation approach, where key ecosystem processes like dispersal and colonisation are facilitated by human intervention, is crucial for the survival of these iconic species, especially in fenced protected areas. The cheetah relocation project is being coordinated by South Africa’s Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) in collaboration with the South African National Biodiversity Institute (Sanbi), South African National Parks (SANParks), and the Cheetah Range Expansion Project run by the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), as well as the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and the Wildlife Institute of India (WII).

Mesopredators – species like cheetah, spotted hyena, African wild dog and black-backed jackal – play a pivotal role in regulating prey populations and maintaining ecological balance. The relationships between cheetahs, hyenas, and other top predators are complex and layered, shaped by competition, coexistence, and the ever-present struggle for survival. These vital mesopredators’ movements and behaviours shape the reserve’s ecological balance in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Cheetahs are skilled hunters but vulnerable to larger predators like hyenas and leopards. They rarely scavenge, relying instead on their speed and agility to secure a meal, devour it, and then move off to avoid competition. Conversely, spotted hyenas are facultative scavengers, meaning they scavenge but do not solely rely on it for survival and reproduction. They’re also skilled hunters, resulting in dietary overlap with cheetahs that creates a dynamic interplay.

To uncover these intricate dynamics, researchers Elizabeth Overton and Marna Visagie from Nelson Mandela University in South Africa are conducting Doctoral and Master studies at Tswalu. Their work delves into the ecological roles of cheetahs and hyenas, and their influence on prey populations, exploring key aspects such as population density, habitat use, and hunting behaviour. Using a combination of radio collars, camera traps, DNA metabarcoding from scat samples, and GPS cluster investigations, they are developing a comprehensive understanding of these mesopredators’ existence, with findings that promise to inform more effective conservation management.

Building on her core fieldwork, Elizabeth recently introduced a compelling new layer of research from the scat samples: an in-depth study of the cheetah microbiome and pathobiome. This genetic research reveals the cheetah’s internal world, the gut microbial communities that influence digestion, immune health and overall resilience. Alongside this, the pathobiome analysis shines a light on disease-related microbial pathways, identifying potential health risks through the presence of pathogenic organisms. By mapping microbial health, researchers gain a deeper understanding of the physiological condition of relocated cheetahs, offering a diagnostic lens to more effectively guide future rewilding efforts.

As the last echoes of the hyena’s movements fade into the night, the Kalahari landscape feels both ancient and alive. With the first light of dawn, we’ll be out there again, sweeping the golden grasslands and russet dunes for that tell-tale beep. Tales yet to unfold.

About the author:

Inaê Guion is a Brazilian biologist and conservation photographer. Holding a PhD in Applied Ecology, her work blends scientific research with compelling visual storytelling to advocate for environmental preservation, focusing on the intricate connections between nature, humanity, and conservation.