THE POWER OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN CONSERVATION

An emotive photograph often speaks louder than any words. We chatted to the multiple award-winning photographer and frequent Tswalu guest, Marcus Westberg, about the immediacy and power of images to tell unforgettable stories and convey conservation messages.

A GROUP OF LOCAL SCHOOL CHILDREN VISITING LEWA WILDLIFE CONSERVANCY FOR THE FIRST TIME.

WHAT IS THE CONNECTION BETWEEN IMAGES, STORIES AND MESSAGES IN THE CONTEXT OF CONSERVATION?

Rather than describing what I do as conservation photography, I prefer the term conservation photojournalism. As the name suggests, this is more about storytelling. Personally, I see conservation photojournalism as documenting the threats faced by wild animals and habitats, as well as what is being done to protect or learn more about them. Much of what I photograph falls into this category. Perhaps surprisingly, a big chunk of it doesn’t involve wildlife. Rangers, researchers, schools, health care and other community projects can all form part of a conservation story.

AN ELEPHANT TRANSLOCATION IN MALAWI: 263 INDIVIDUALS WERE MOVED FROM LIWONDE TO KASUNGU NATIONAL PARK.

DID YOU SET OUT TO BECOME A PHOTOJOURNALIST?

Twelve years ago, I was on an academic path. While conducting a research project in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, I began to have doubts. For one thing, what I was doing was so slow. It would be years before anything I was researching or documenting would be published. Even then, would anyone other than other academics read it? Probably not.

With rather astonishing naivety – at this point I was nearly broke and had very little experience as a photographer – I decided that documenting the work of others would be a more effective way for me to make a difference. To be honest, I also thought it would be more fun. Somehow, it actually worked out, though it took quite a few years. I bartered my way around southern Africa until I eventually reached a point where what I was doing had become a viable career. Today, most of my time is spent documenting conservation-related subjects.

With incredible naivety – I was nearly broke when I got into photography – I decided that documenting the work of others would be a more effective way to make a difference. I also thought it would be fun! Somehow, it worked out. I bartered my way around southern Africa until I eventually reached a point where what I was doing had become a viable career. Today, most of my time is spent documenting conservation-related subjects.

ZAMBIA CARNIVORE PROGRAMME’S THANDIWE MWEETWA OVERSEES ONE OF HER TEAM MEMBERS WHILE MONITORING AFRICAN WILD DOGS IN SOUTH LUANGWA NATIONAL PARK, ZAMBIA.

CAN A SINGLE PHOTO REALLY HAVE AN IMPACT OR STAND OUT AMONG THE THOUSANDS WE SEE EVERY DAY?

I think it is just as tempting to overestimate the power of photography as it is to underestimate it. There are a lot of photos in circulation, and our collective attention span seems to be getting shorter by the day. To assume that a particular photo is going to “change the world” is ambitious. Besides, that idea is all too often used as an excuse for behaving unethically around wildlife. Perhaps there are times when the ends justify the means, but I do think we should live as we preach, and that starts with respecting both wild animals and fellow humans.

Still, photography has an immediacy about it and can definitely convey a message in a very powerful way. It can make you feel something – and that effect is immediate.

A RESCUED PUTTY-NOSED MONKEY WITH A RANGER IN ODZALA-KAKUA NATIONAL PARK, REPUBLIC OF CONGO

HAS ANY SINGLE IMAGE EVER ROCKED THE CONSERVATION WORLD?

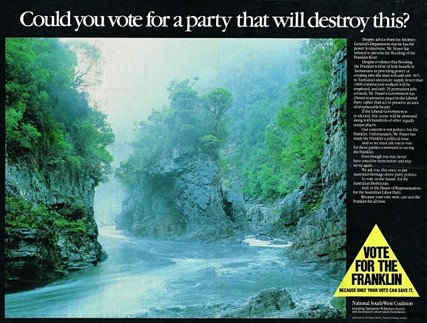

It does happen. An early inspiration for me was the way an image by Tasmanian photographer Peter Dombrovskis helped decide an Australian election and prevent the damming of the wonderful Franklin River in 1983, the year I was born. More recently, I’d say Steve Winter’s iconic photograph of a mountain lion in front of the Hollywood sign in Los Angeles, or Brent Stirton’s harrowing photo of the murdered silverback gorilla Senkwekwe being carried out of Virunga National Park on a bamboo stretcher. Those had real and measurable effects on conservation efforts. More often, though, it’s not about a single image but collective efforts.

A FULL-PAGE AD TAKEN OUT BY THE WILDERNESS SOCIETY AHEAD OF THE 1983 FEDERAL ELECTION IN AUSTRALIA.

MORE BROADLY, HOW CAN PHOTOGRAPHY CONTRIBUTE TO CONSERVATION?

Images of beautiful places and creatures remind us of just how fascinating the natural world is, and of what we stand to lose. When it comes to conservation photojournalism, editorial stories in print or online spring to mind. Like many, I was mesmerized by the photographs in National Geographic as a child.

The right story in the right publication can have a massive impact on public opinion, too. It’s a lot more difficult to get away with irregular or exploitative behaviour if it is in the public eye, so that exposure really matters. Furthermore, feature stories provide people around the world with role models by highlighting the importance of conservationists, rangers, teachers, and researchers in the field.

Most of my work is for conservation organisations. There are countless ways in which these companies or not-for-profits incorporate strong images, ranging from annual reports and donor updates to websites, social media and funding applications. This might mean that many of my images are not seen by the public at large. That’s unfortunate, but I don’t really mind as long as they fulfill their purpose.

Evocative images can also be used to raise funding for conservation – Prints For Wildlife, Vital Impacts and the Remembering Wildlife books are great examples of this.

VETERINARIANS CONDUCTING A HEALTH EXAMINATION ON AN ORPHANED MOUNTAIN GORILLA IN VIRUNGA NATIONAL PARK, DR CONGO.

GIVE US A FEW EXAMPLES OF IMAGES YOU’VE TAKEN THAT HAVE HAD AN IMPACT?

I’m hesitant to draw too many specific conclusions about impact. I think photography is generally a way to enhance impact rather than create it, because people have to care about an issue in order to want to take action. There is a Swedish expression that roughly translates to “many small streams combine to make a big river”, and I guess that is the light in which I see my contributions.

Having said that, for the last few years I have been documenting the clear-cutting of Sweden’s forests, and I think it is fair to say that those photographs have had a significant impact. It is something that hadn’t really been photographed professionally before, at least not on that scale, so my images have been published and used extensively both in Sweden and abroad. They have won a few awards, too. Most importantly, many of the people doing the actual fighting for our forests have reached out. If they find them as useful as they say they do, that’s all I need to know. They may only be one of those little streams, but at least I know that they definitely contributed water to that big river.

A 2021 ARTICLE ABOUT SWEDEN’S UNSUSTAINABLE FORESTRY PRACTICES IN THE GUARDIAN.

YOU ARE A REGULAR VISITOR TO TSWALU. IN TERMS OF CONSERVATION PHOTOJOURNALISM, WHAT IS THERE TO KEEP YOU BUSY AND INTERESTED ON THIS RESERVE?

So much! Tswalu is a serious, long-term rewilding endeavour, surrounded by farms and mines, in the fragile Kalahari ecosystem. I love spending time with researchers in the field and highlighting the contribution of the Tswalu Foundation’s findings to conservation. Then there is the hands-on conservation work, from wildlife monitoring and rhino notching to the reintroduction of new species. More recently, I’ve started documenting the reserve’s sustainability journey and community projects, from the school to the health care centre. I have only scratched the surface and look forward to my next visit.

A RESEARCH TEAM FROM BLOEMFONTEIN CONDUCTING A NON-INTRUSIVE SURVEY OF SMALL MAMMALS AT TSWALU.

References:

https://urth.co/magazine/the-photo-that-saved-the-franklin-river

All images by Marcus Westberg. Keep following @marcuswestbergphotograpy on instagram